We didn’t realize it at the time, but our visit to the city of Derry in Northern Ireland a week ago today was on the weekend marking the 39th anniversary of the Bloody Sunday massacre. I know, probably not the most inviting first sentence to a Friday afternoon before Superbowl weekend post, but bear with me!

After a gorgeous drive from our accommodations on the North Antrim coast, a place I will cover in another post, we arrived just outside the walls of Derry at the tourist office. A free map in our hands, we set out on our walk.

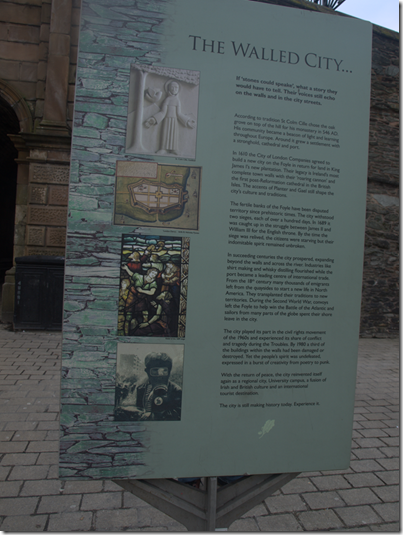

Derry is the only remaining completely walled-in city in Europe. It’s walls, which were built between 1614-1619, cover about 1.5 km and have several gates at which people and vehicles can get in and out of the city. We entered at the Ferryquay Gate and started our walk there. The walls are not just walls, but walkways that you actually walk on top of, so you can see for miles around by looking over the stone.

The tourist office in Derry offers guided walking tours, but the way the walls are set up, with plaques throughout, explaining each area, it is easy to take a self-guided tour. I have a thing against group tours, and we were content to go on our own. For a complete background on the walls, I found this site from the Derry City Council to be interesting.

Looking at the city within the walls, you can see that it has changed immensely over the years, now offering all sorts of clothing shops, cafes, restaurants, and pubs.

Looking out, through holes in the thick stone walls, originally meant for soldiers with guns and for cannons, you can see the various neighborhoods that surround this city on a hill.

To the North, near the Butcher’s Gate, there is the sprawling neighborhood called the Bogside. The Bogside is a predominantly Catholic neighborhood, and the scene of the Bloody Sunday massacre.

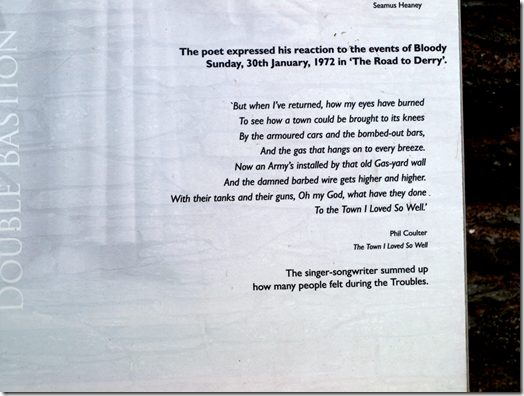

One of the informational plaques near the area shares the words of a song written by singer-songwriter Phil Coulter, a native of Derry’s Bogside. The Town I Loved So Well is a well-known song in Ireland, and I have always liked it but never really was able to put it into context until our visit to Derry.

You can listen to the song by clicking on the You Tube clip below.

Just around the bend in the walk along Derry’s walls, the murals and colors you can see, even from a distance, are completely different. On this side is a largely Protestant area that historically housed Loyalists, those residents of Northern Ireland who want to remain part of the United Kingdom

Even the curbs and lamp posts are painted in Union Jack red, white, and blue.

I had chills through most of the walk, especially seeing signs like these, and realizing all of the lives that have been lost or destroyed. It was especially strange to see how close these neighborhoods are to one another. In Boston terms, it would be like Beacon Hill being at war with Back Bay.

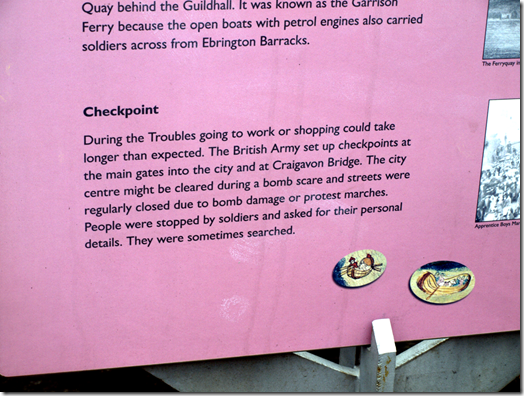

More information on life in Derry during The Troubles was outlined in the above sign. Even being there, I found it hard to imagine growing up in a place with military checkpoints. As trite as it sounds, it made me incredibly grateful for the freedoms I have always taken for granted.

As we walked on, I noticed shamrocks growing in the cracks of the walls ![]() And we came across this statue. Originally part of a series of three statues by Antony Gormley, this artwork caused controversy and tension on both sides of the divide as it is intended to show the similarities that unite the people of Derry. It looks the same on both sides, each having a face, and they were originally placed looking out of the walls on different sides into the Catholic and Protestant neighborhoods. The eyes are hollow all the way through, so to give those who encounter the statue the chance to look through the eyes of the other.

And we came across this statue. Originally part of a series of three statues by Antony Gormley, this artwork caused controversy and tension on both sides of the divide as it is intended to show the similarities that unite the people of Derry. It looks the same on both sides, each having a face, and they were originally placed looking out of the walls on different sides into the Catholic and Protestant neighborhoods. The eyes are hollow all the way through, so to give those who encounter the statue the chance to look through the eyes of the other.

After our walk, we decided to drive around the outside of the city walls and into the Bogside, starting at what is known as Free Derry Corner. A sign that announces “You are now entering Free Derry.” and a mural of a man in a gas mask mark this corner. As in Belfast, as you enter the Irish Catholic portion of Derry, you start to see these murals, and, as is normal in the Republic of Ireland, signs in both Irish and English.

While some of the murals in Derry remembered the 1981 hunger strike, most remember the civilian victims of violence on Bloody Sunday and the tumultuous years that surrounded the event.

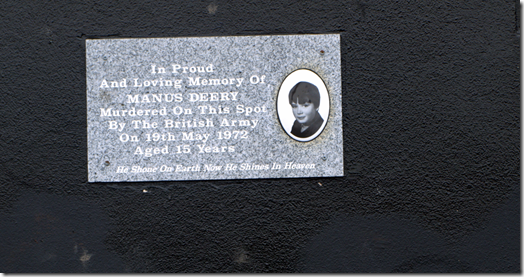

We turned into a parking lot of a dilapidated building to make a U-turn and randomly came across this plaque, remembering a 15 year old boy killed on that spot. It seemed there was sorrow on every corner.

I think the most emotional part was driving along the road that housed many of the Bloody Sunday murals. People living in the Bogside during this time were subject to British soldiers breaking down their doors in the middle of the night to question and intern them, often without reason or proof or a warrant. In the mural on the left below, you can see the soldier breaking down a door.

The events of Bloody Sunday have been disputed over the years, but it began with a march for civil rights and against illegal internment. Part of a Wikipedia page on the events of the day state the following:

“Thirteen people were shot and killed, with another man later dying of his wounds. The official army position, backed by the British Home Secretary the next day in the House of Commons, was that the paratroopers had reacted to the gun and nail bomb attacks from suspected IRA members. However, all eyewitnesses (apart from the soldiers), including marchers, local residents, and British and Irish journalists present, maintain that soldiers fired into an unarmed crowd, or were aiming at fleeing people and those tending the wounded, whereas the soldiers themselves were not fired upon. No British soldier was wounded by gunfire or reported any injuries, nor were any bullets or nail bombs recovered to back up their claims.”

Many of the dead were just 17 years old, and some had been shot in the back as they ran away. Still, for decades, it was the dead protesters who were blamed while the soldiers walked free.

In June of 2010, over 38 years later, a British inquiry into the events of Bloody Sunday exonerated the dead and placed the blame on the British soldiers, calling the massacre “unjustified and unjustifiable”.

This past Sunday, just two days after our visit, the civil rights march that was begun in 1972 was completed by families, friends, neighbors, and supporters of those who were murdered on Bloody Sunday in what is thought to be the last march of its kind.

Tags: Bloody Sunday, Derry, history, Northern Ireland, Travel

-

It’s very powerful to be a witness, even now, to places like this. It is powerful to remember how hard it is to live in some places, to imagine what it must be like to live amid violence daily. A very thoughtful post, thank you.

-

Pingback from Our Best Selves on May 3, 2011 at 12:34 am

11 comments

Comments feed for this article

Trackback link: http://traveleatlove.me/2011/02/walking-the-walls-of-derry/trackback/